Brief: Cryptographically Relevant Quantum Computers (CRQC)

A cryptographically relevant quantum computer is one capable of breaking widely used public-key encryption by running algorithms like Shor's at scale.

It requires fault-tolerant operation, stable logical qubits, and enough coherence to complete deep quantum circuits. While no such machines exist today, their eventual arrival poses a direct threat to current cryptographic infrastructure.

How is a CRQC different from the quantum computers we have today?

Not all quantum computers are cryptographically relevant. That's an important distinction—because the machines available today are fundamentally limited.

Most current systems fall into a category called NISQ, or noisy intermediate-scale quantum.

These machines can run small-scale experiments. They can demonstrate quantum behavior. But they aren't stable or powerful enough to run cryptographic attacks. Not even close.

Why not?

Because NISQ devices are error-prone.

They can't correct those errors in real time. And they don't maintain coherent operations long enough to run large, structured algorithms. That means they're great for research, but not useful for breaking encryption.

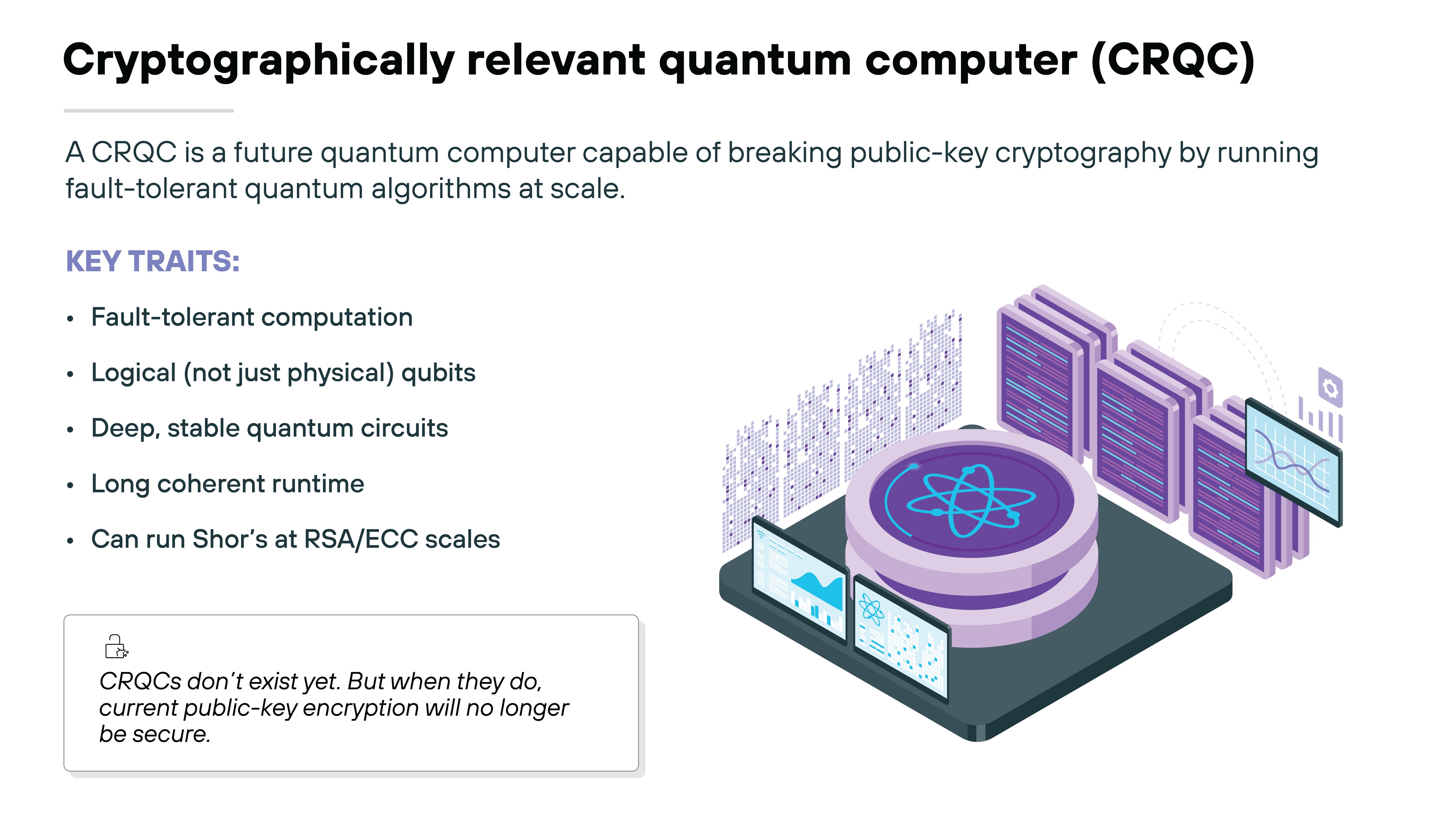

A cryptographically relevant quantum computer—also called a CRQC—represents a completely different threshold. It's not just a bigger version of today's machines. It's a future class of hardware capable of performing complex, fault-tolerant quantum computations at scale.

In other words:

A CRQC doesn't exist yet. But it's the point where quantum computers stop being experimental and start becoming a real-world security threat.

What would a quantum computer need to become cryptographically relevant?

The term cryptographically relevant isn't about hype. It's about thresholds.

For a quantum computer to break today's public-key cryptography, it would need to reach a very specific level of maturity. And that bar is higher than most people think.

Here's why:

It's not enough to increase the number of qubits.

The machine also needs to be fault-tolerant.

That means it can detect and correct its own errors during a computation. Without that, deeper algorithms like Shor's simply don't work.

Plus, fault tolerance requires another step:

Logical qubits.

A CRQC would likely need thousands of logical qubits.

Achieving that could take millions of physical qubits. Because each logical qubit demands error correction across dozens or hundreds of physical qubits, depending on error rates.

Then there's runtime.

A CRQC would need to maintain coherent, error-corrected operation long enough to finish the full circuit depth required to factor an RSA key or solve an elliptic-curve discrete log problem.

To put it more simply: it would need to run complex quantum calculations cleanly and reliably—without drifting off course or breaking down. That means running cleanly across billions of quantum gate operations. Possibly for hours.

Important:

We're not just waiting for more power. We're waiting for stability, precision, and time. Those are the real barriers.

Until a quantum system can meet all three, it's not cryptographically relevant. It may be useful for other things. But it won't threaten encryption at scale. Yet.

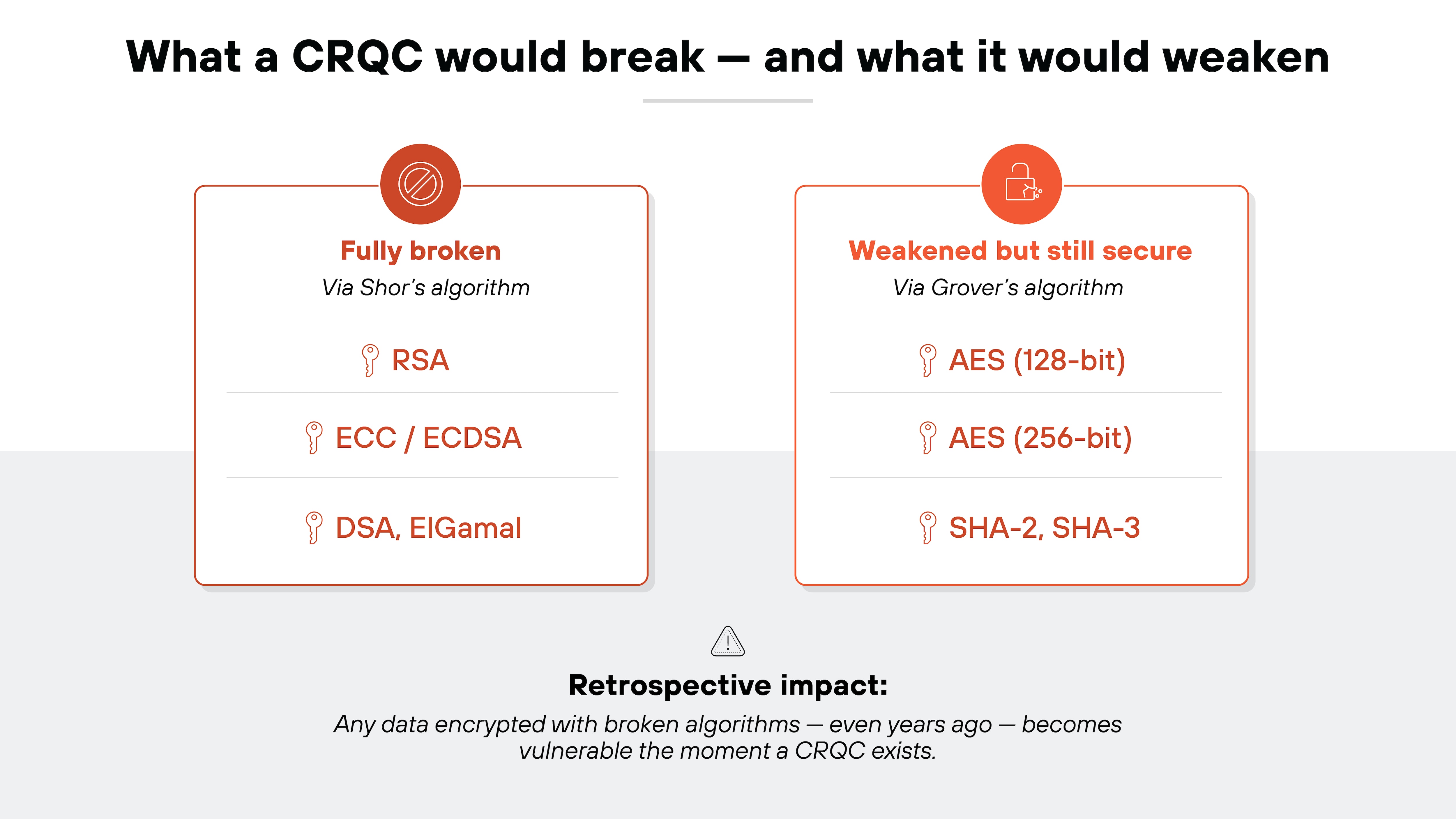

Which encryption methods would a CRQC break?

A cryptographically relevant quantum computer wouldn't disrupt everything. But it would break the cryptographic foundations that most digital systems rely on today.

Let's start with what would be directly compromised.

All widely deployed public-key cryptography would be broken.

That includes RSA, which is used for secure connections and key exchanges. It also includes elliptic-curve cryptography, which underpins modern authentication, digital signatures, and encryption schemes.

These algorithms rely on mathematical problems—like factoring and discrete logarithms—that quantum algorithms could solve efficiently at scale.

In other words:

Once a quantum computer can run Shor's algorithm against real-world key sizes, public-key cryptography as we know it becomes insecure.

Symmetric encryption is a different story.

It wouldn't be broken outright. But it would be weakened. A quantum computer could use Grover's algorithm to reduce the effective security level. That means 128-bit symmetric keys could offer just 64 bits of security in a quantum scenario. Hash functions would see similar reductions in collision or preimage resistance.

Critical point:

These changes don't happen gradually. The moment a CRQC exists, this impact becomes real. And it applies retroactively to any encrypted data that's already been captured. Which is why quantum security has become such a critical initiative.

Why does the CRQC threat matter now?

It's easy to assume this is a future problem. After all, cryptographically relevant quantum computers don't exist yet.

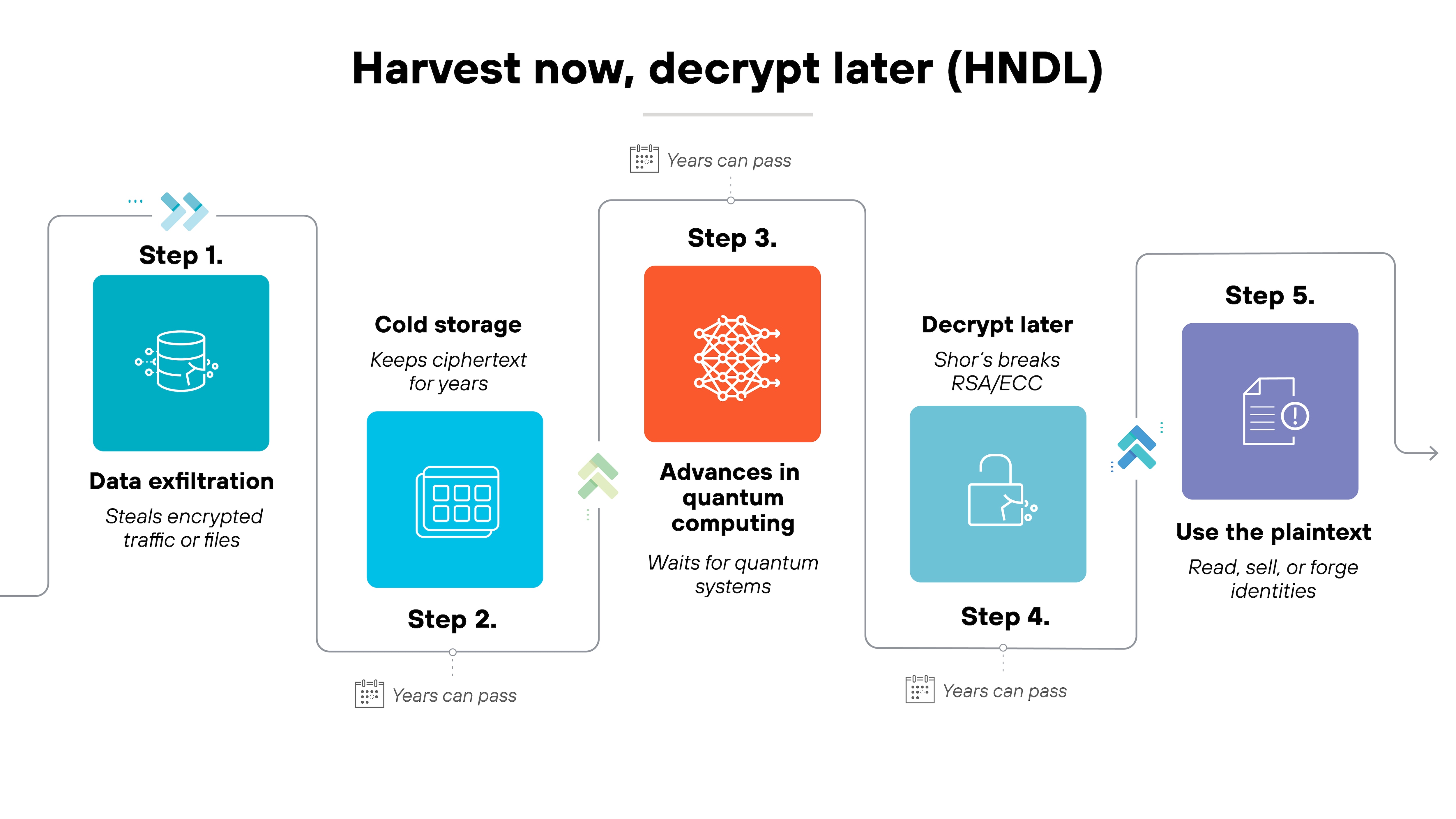

But the threat is already active. Just in a different way.

The risk comes from what's called harvest now, decrypt later.

Encrypted data can be intercepted and stored today. That data might not be readable now. But once a CRQC becomes available, any old traffic encrypted with broken algorithms can be decrypted. The threat is delayed, not prevented.

This matters most for long-lived data. Think government records, medical histories, trade secrets, or source code. Anything with value that extends beyond a few years is at risk.

Here's why:

Even if the quantum threat is ten years away, the damage could already be done by then. And some secrets—like private keys or firmware signatures—don't expire. If they're ever compromised, the effect is permanent.

Digital signatures have the same issue. Once forged, trust breaks down. And you can't go back and revalidate the past.

In short:

The CRQC threat doesn't begin the day one gets built. It begins the moment your sensitive data gets captured—if it's protected by cryptography that won't hold up when quantum finally arrives.

- Harvest Now, Decrypt Later (HNDL): The Quantum-Era Threat

- 8 Quantum Computing Cybersecurity Risks [+ Protection Tips]

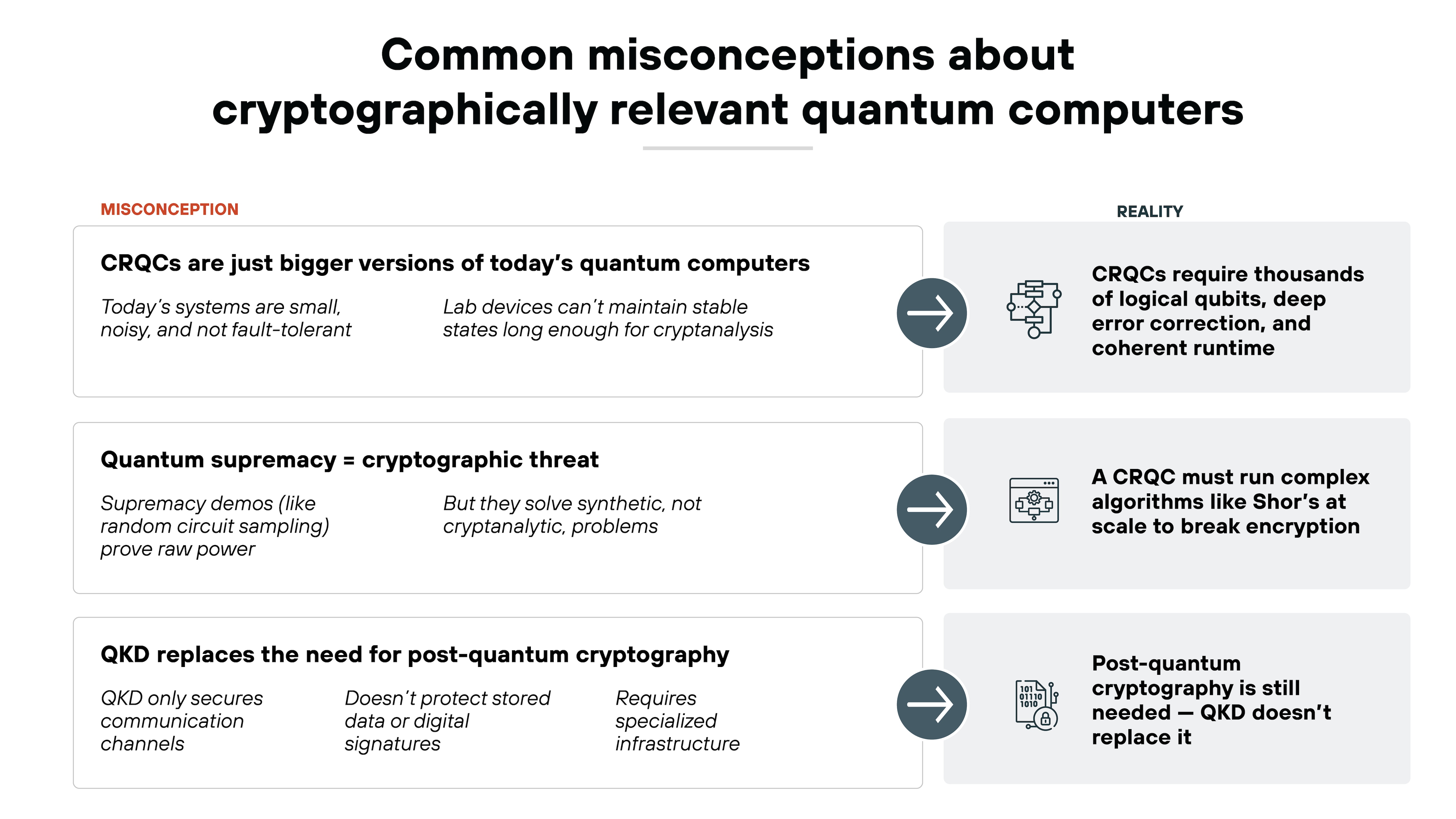

What are common misconceptions about CRQCs?

There's growing interest in quantum computing. But there's also confusion. Especially around what a cryptographically relevant quantum computer actually is.

So let's clear a few things up.

A CRQC isn’t just a bigger version of today’s quantum devices.

It's not the same as what researchers use in labs now. Those systems are still noisy, limited, and experimental. CRQCs require something entirely different: stability, scale, and fault tolerance.

They also aren't the same as quantum-supremacy machines.

Demonstrating quantum advantage on a narrow task doesn't mean a system can run cryptographic attacks. That's a much higher bar.

Another common misconception? That quantum key distribution (QKD) replaces the need for post-quantum cryptography.

It doesn't. QKD is a communication protocol. It doesn't protect stored data or signatures. And it requires specialized infrastructure, not just a software update.

To sum up:

Not every quantum breakthrough is a cryptographic threat.

CRQCs are real, but they're specific. And understanding the distinction is what helps organizations prepare, without overreacting.