-

What Is a Cyber Attack?

- Threat Overview: Cyber Attacks

- Cyber Attack Types at a Glance

- Global Cyber Attack Trends

- Cyber Attack Taxonomy

- Threat-Actor Landscape

- Attack Lifecycle and Methodologies

- Technical Deep Dives

- Cyber Attack Case Studies

- Tools, Platforms, and Infrastructure

- The Effect of Cyber Attacks

- Detection, Response, and Intelligence

- Emerging Cyber Attack Trends

- Testing and Validation

- Metrics and Continuous Improvement

- Cyber Attack FAQs

- Dark Web Leak Sites: Key Insights for Security Decision Makers

-

What Is a Zero-Day Attack? Risks, Examples, and Prevention

- Zero-Day Attacks Explained

- Zero-Day Vulnerability vs. Zero-Day Attack vs. CVE

- How Zero-Day Exploits Work

- Common Zero-Day Attack Vectors

- Why Zero-Day Attacks Are So Effective and Their Consequences

- How to Prevent and Mitigate Zero-Day Attacks

- The Role of AI in Zero-Day Defense

- Real-World Examples of Zero-Day Attacks

- Zero-Day Attacks FAQs

-

What Is Lateral Movement?

- Why Attackers Use Lateral Movement

- How Do Lateral Movement Attacks Work?

- Stages of a Lateral Movement Attack

- Techniques Used in Lateral Movement

- Detection Strategies for Lateral Movement

- Tools to Prevent Lateral Movement

- Best Practices for Defense

- Recent Trends in Lateral Movement Attacks

- Industry-Specific Challenges

- Compliance and Regulatory Requirements

- Financial Impact and ROI Considerations

- Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Lateral Movement FAQs

-

What is a Botnet?

- How Botnets Work

- Why are Botnets Created?

- What are Botnets Used For?

- Types of Botnets

- Signs Your Device May Be in a Botnet

- How to Protect Against Botnets

- Why Botnets Lead to Long-Term Intrusions

- How To Disable a Botnet

- Tools and Techniques for Botnet Defense

- Real-World Examples of Botnets

- Botnet FAQs

- What is a Payload-Based Signature?

-

What is Spyware?

- Cybercrime: The Underground Economy

-

What Is Cross-Site Scripting (XSS)?

- XSS Explained

- Evolution in Attack Complexity

- Anatomy of a Cross-Site Scripting Attack

- Integration in the Attack Lifecycle

- Widespread Exposure in the Wild

- Cross-Site Scripting Detection and Indicators

- Prevention and Mitigation

- Response and Recovery Post XSS Attack

- Strategic Cross-Site Scripting Risk Perspective

- Cross-Site Scripting FAQs

- What Is a Dictionary Attack?

- What Is a Credential-Based Attack?

-

What Is a Denial of Service (DoS) Attack?

- How Denial-of-Service Attacks Work

- Denial-of-Service in Adversary Campaigns

- Real-World Denial-of-Service Attacks

- Detection and Indicators of Denial-of-Service Attacks

- Prevention and Mitigation of Denial-of-Service Attacks

- Response and Recovery from Denial-of-Service Attacks

- Operationalizing Denial-of-Service Defense

- DoS Attack FAQs

- What Is Hacktivism?

- What Is a DDoS Attack?

-

What Is CSRF (Cross-Site Request Forgery)?

- CSRF Explained

- How Cross-Site Request Forgery Works

- Where CSRF Fits in the Broader Attack Lifecycle

- CSRF in Real-World Exploits

- Detecting CSRF Through Behavioral and Telemetry Signals

- Defending Against Cross-Site Request Forgery

- Responding to a CSRF Incident

- CSRF as a Strategic Business Risk

- Key Priorities for CSRF Defense and Resilience

- Cross-Site Request Forgery FAQs

- What Is Spear Phishing?

-

What Is Brute Force?

- How Brute Force Functions as a Threat

- How Brute Force Works in Practice

- Brute Force in Multistage Attack Campaigns

- Real-World Brute Force Campaigns and Outcomes

- Detection Patterns in Brute Force Attacks

- Practical Defense Against Brute Force Attacks

- Response and Recovery After a Brute Force Incident

- Brute Force Attack FAQs

- What is a Command and Control Attack?

- What Is an Advanced Persistent Threat?

- What is an Exploit Kit?

- What Is Credential Stuffing?

-

What is Social Engineering?

- The Role of Human Psychology in Social Engineering

- How Has Social Engineering Evolved?

- How Does Social Engineering Work?

- Phishing vs Social Engineering

- What is BEC (Business Email Compromise)?

- Notable Social Engineering Incidents

- Social Engineering Prevention

- Consequences of Social Engineering

- Social Engineering FAQs

-

What Is a Honeypot?

- Threat Overview: Honeypot

- Honeypot Exploitation and Manipulation Techniques

- Positioning Honeypots in the Adversary Kill Chain

- Honeypots in Practice: Breaches, Deception, and Blowback

- Detecting Honeypot Manipulation and Adversary Tactics

- Safeguards Against Honeypot Abuse and Exposure

- Responding to Honeypot Exploitation or Compromise

- Honeypot FAQs

- What Is Password Spraying?

- How to Break the Cyber Attack Lifecycle

-

What Is Phishing?

- Phishing Explained

- The Evolution of Phishing

- The Anatomy of a Phishing Attack

- Why Phishing Is Difficult to Detect

- Types of Phishing

- Phishing Adversaries and Motives

- The Psychology of Exploitation

- Lessons from Phishing Incidents

- Building a Modern Security Stack Against Phishing

- Building Organizational Immunity

- Phishing FAQ

- What Is a Rootkit?

- Browser Cryptocurrency Mining

- What Is Pretexting?

- What Is Cryptojacking?

What Is Smishing?

A combination of SMS–short messaging service, or texting–and phishing, smishing refers to text messages sent by attackers to gain personal and sensitive information. Like spear phishing, smishing attacks rely on tricking users into clicking a link to provide sensitive information, like login credentials which can be used to access target systems, or even deposit malware.

This method of attacking has recently become more popular due to the ease of gathering phone numbers, the prevalence of smartphones, and the inferred trust of a text message over a traditional email. While emails can contain any number of letters or special characters, phone numbers around the globe follow specific patterns, such as the three-four-three 10-digit pattern in the U.S., and attackers can try different combinations or send out blasts to a specific range. Additionally, phone numbers are often associated with social media, making them easier to find while also providing attackers a repository of information to make smishing attempts more personalized.

Scammers are also succeeding due to the relationship between a user and their phone. Whether they’re on the go or distracted with something else, users are more likely to trust their smartphones or skim a message rather than reading it carefully. To best protect against smishing – and phishing scams in general – it’s important for users to scrutinize phone numbers, read messages carefully, and never click on an unfamiliar link.

How to Spot a Smishing Attempt

Unfortunately, there is no shortage of phishing attacks on any device. Whether cybercriminals are hunting for credit cards, login credentials, or any other bits of sensitive information, SMS phishing attempts are threats that mobile users need to be prepared for.

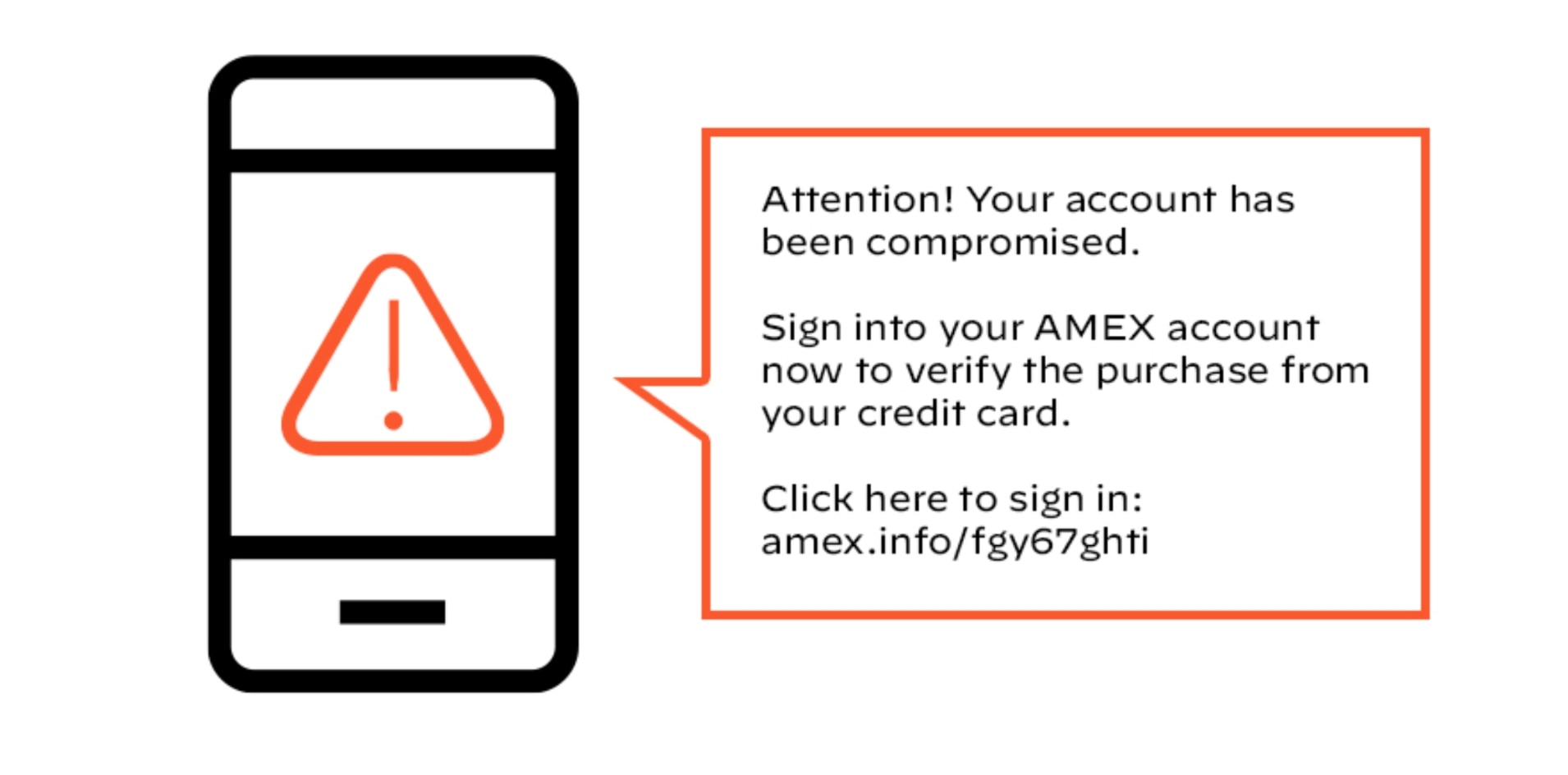

A common smishing attack involves banking services. Posing as a legitimate financial institution, these text messages can appear to be time sensitive to encourage victims to log in without thinking critically.

Figure 1: Sample text message alerting victim of account compromise, encouraging them to sign in with link provided

The best way to react to these types of messages is to bypass the link and go directly to the bank itself. Go to the bank’s website, log in to their app or even call a local branch to verify if there are any issues with a bank account.

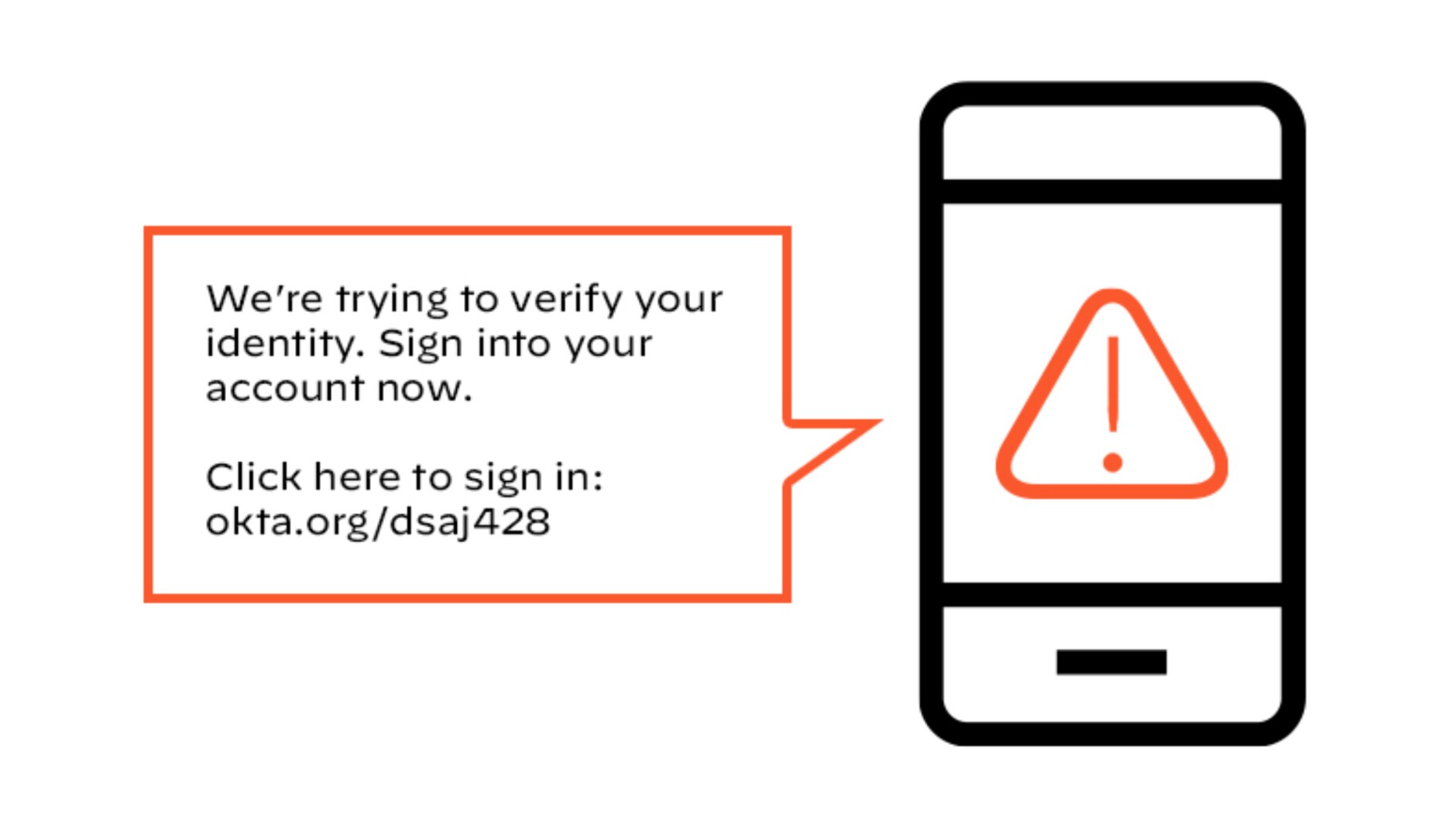

Another example of smishing attacks takes advantage of multifactor authentication (MFA). Attackers will send credential text messages to users, encouraging them to sign in. Hackers build these malicious domains to look like the authentic credential sites that users are familiar with.

Figure 2: Sample text message encouraging a victim to sign in at the provided link so they can verify their identity.

With attacks like these, users have to think carefully. Have they signed in to something recently? Is this the normal way for them to verify their identity? As with banking institutions, it’s best to go directly to the source and verify. It’s important to note that while some attackers are taking advantage of MFA, the added security of MFA is still an incredibly important defense against cybercrime.

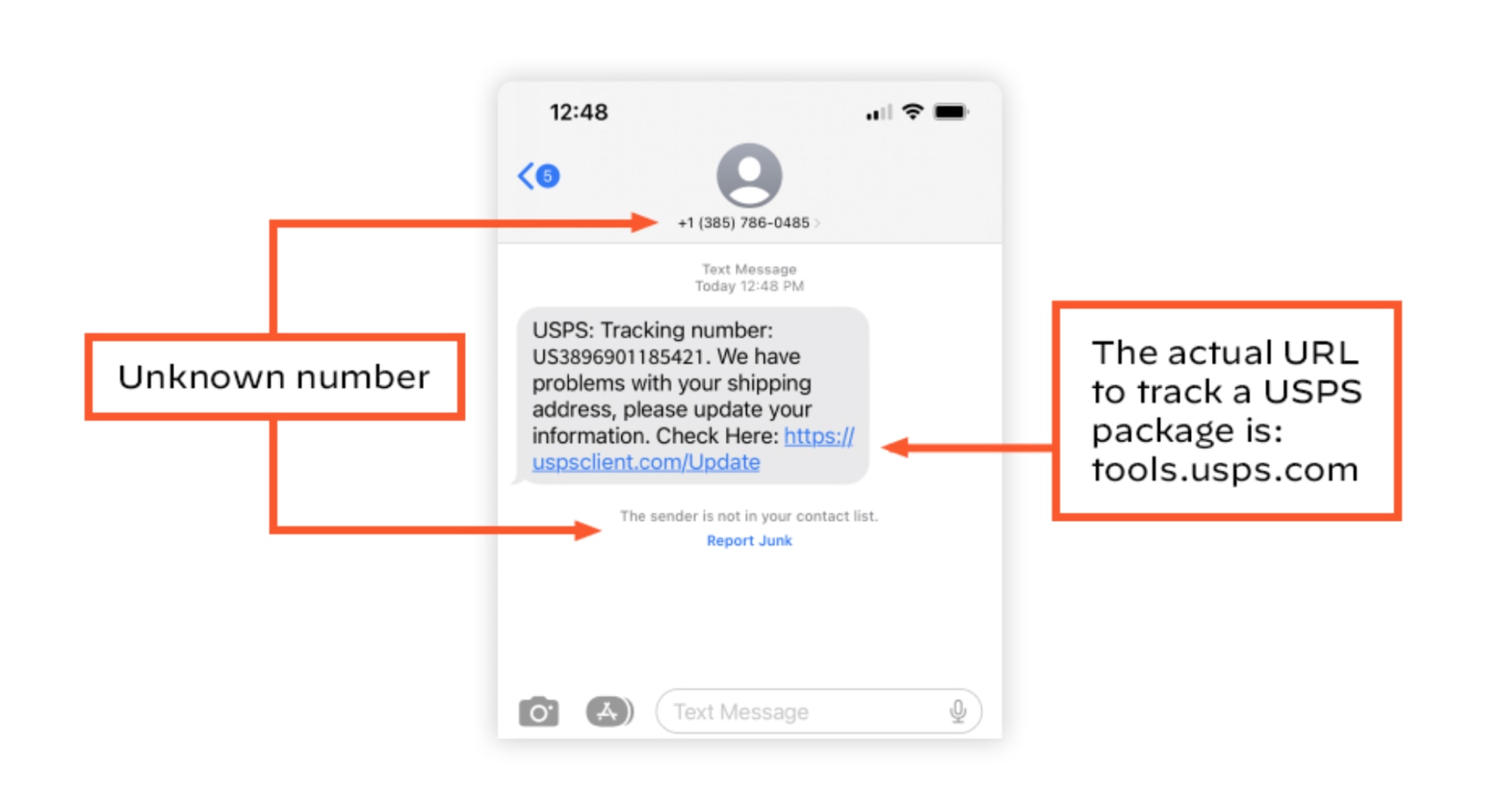

Figure 3 is a realistic example based on a smishing message that one of our employees received.

Figure 3: Screenshot of a smishing attempt with the strange number and incorrect link highlighted

How to Avoid Being Smished

As mentioned earlier, one of the best techniques to avoid being smished is being critical with the text messages you receive. Never click on a link you’re unfamiliar with and don’t feel obligated to respond to a strange text from a number you don’t recognize. If you receive a smishing text in the U.S., you can report it to reportfraud.ftc.gov.

For security professionals, it is important to implement user education. Training and testing your company on how to identify phishing and smishing will greatly reduce the likelihood of a successful phish attempt.

Taking it a step further, another important piece of this puzzle is the organization-wide adoption of a Zero Trust stance. It’s important to monitor your environment with the understanding that nothing should be implicitly trusted – anything in your network can be used against you. Products like endpoint detection and response (EDR) provide broad visibility and machine learning (ML)-based detection for real-time threat analysis. An EDR product can be paired with a security orchestration, automation, and response (SOAR) platform for automation-based threat response.

Learn more about how endpoint and network security work together.

Sign up for a Cortex demo to see how XDR and XSOAR can improve your security posture.